(Thomas Froese Photo)

(The Hamilton Spectator, Saturday, April 20, 2019)

SAVANNAH, GEORGIA – The comedy of life, the absolute comedy, is that the God of this weekend, the one who walked and slept and bled and cried and, sure, laughed among us, is still found in the most unexpected places.

This comedy is different than the comedy of, say, Saturday Night Live. It’s more sardonic. More cutting. This comedy might set some captives free, but also start some fires, or at least make you reach for a Gravol if you have a weak stomach.

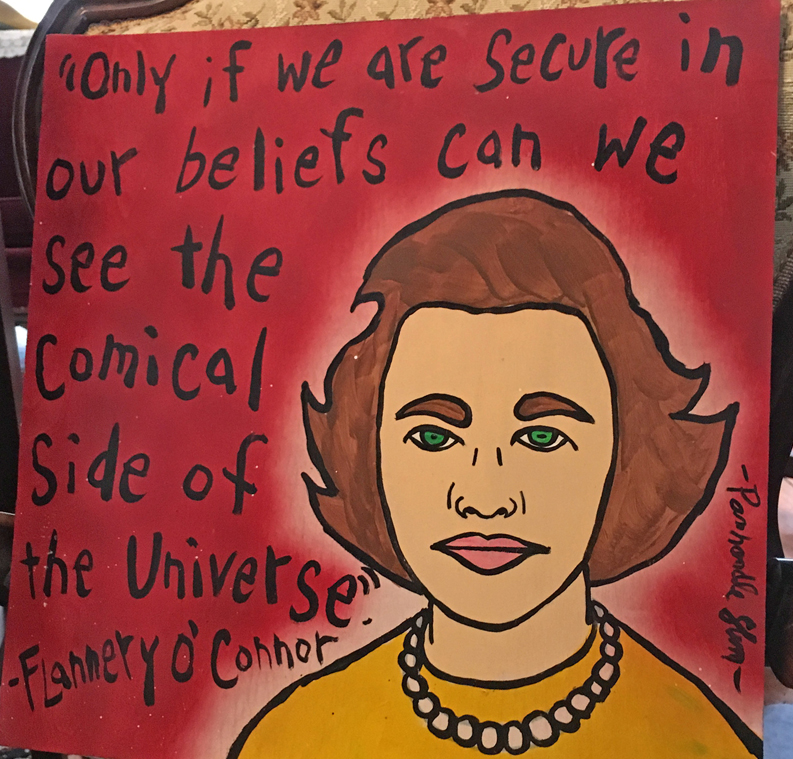

It’s often expressed in the awful honesty of the artists, in this case Flannery O’Connor, a writer who, like many of us, knew that life is comedy, but tragedy also. Darkness is as inevitable as the sunrise, God can seem empty and distant, and none of us do well with this.

This is life’s two-sided coin. As Stephen Hawking put it, “Life would be tragic if it weren’t funny.” Thankfully, Stephen, even in suffering, lived. Nobody put him down with an injection of secobarbital. Thankfully Flannery, in her wild humour, lived too, even while suffering, dead at just 39 from lupus, the horrible disease that also took her father when she was 15.

Yes, Mary Flannery O’Connor was one of those people who believed with some passion that the universe – you and me and every living thing – is charged with God, that is the God of Easter: the mysterious God-Man, Jesus, of Nazareth, who apparently suffered and died among us, then apparently rose to life, and, in this, apparently had the last laugh over both suffering and death.

This fervour gave Flannery a reputation, naturally, but she wore it well. “You shall know the truth and the truth shall make you odd,” she said. Then, in her brief allotted time, she wrote like the devil about it all. She wrote particularly about God’s grace, that is God’s forgiveness, and how it’s understood through brokenness.

Of course, there’s nothing worse than a broken person who’s unaware of their own broken nature. So Flannery’s stories are filled with deceptively backwards characters – you might know one or two yourself – who suffer from that worst of the seven deadly sins, pride, and live in their own sort of self-made prison.

For example in “A Good Man is Hard to Find” a certain grandmother is hopelessly blind in this regard. She diverts her family on a leisurely and ill-fated drive from Georgia to Florida, unwittingly into the hands of a murderous criminal. The entire family is killed before the old woman herself has her moment of reckoning with the so-called Misfit.

“Jesus was the one who raised the dead. And he shouldn’t have done it. He showed everything off balance,” the twisted Misfit says, before he puts three bullets in the grandmother’s chest. He leaves her very dead, but smiling up at the blue sky. Horrible, for sure. But that old woman’s smile. With a hint of receiving that Easterish forgiveness.

Yes, terrible and wonderful things will happen to each of us. And as it is, I also recently drove through Georgia and Florida. And while I found no murderous Misfit – the story is fictitious after all – I did find myself inside Flannery’s very real childhood home.

There I stood and stared through her old bedroom window across the street to where I’d just also visited, Savannah’s historic Cathedral of St. John the Baptist, a neighbourhood touchpoint that had a profound impact on young Flannery. In a way, I also stared into what you’ve just read, the great reversal that Flannery loved to explore: how up is down, how the last will be first, how you find your life by giving it up.

Of course, not everyone is versed with Flannery’s stories, how they splay and lay bare the ridiculous and hopeful innards of human nature. Nor is everyone aware of the societal contribution left by her work, among the richest in the English literary canon.

How good it is, then, to be able to have stories, so key to our experience, so that we can better understand just why on God’s good and violent earth there are so many people – an estimated 2.2 billion including the lukewarm and half-hearted and certainly broken – who are worshipping and celebrating this Easter.

To be sure, it is all odd. Then again, is the supernatural anything less?