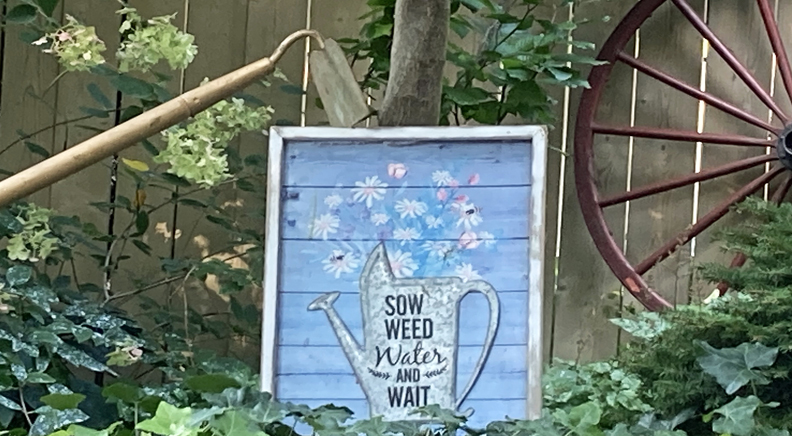

(Thomas Froese Photo)

The writer’s backyard with the golden hoe that’s been in the family for several decades.

(The Hamilton Spectator – Saturday August 31, 2024)

Lately I’ve been thinking about being a billionaire.

Billionaires sometimes jump off tall buildings after cutting their kids from the will. Read John Grisham’s novel “The Testament” for more on this. No, the billionaire life isn’t for everyone.

When it comes to money and work and these things, I just tell my kids, “Kids. Be patient.” I don’t remind them of the day that doctor assessed me and, somewhat shocked, said that I’d live to be 100. (And maybe outlive said kids and their inheritance.)

My own formal relationship with money and work started in the Walper Hotel in Kitchener. It’s a long-standing place on the corner of King and Queen streets that’s hosted everyone from Al Capone to many of Canada’s prime ministers.

My job was to wash everything in its banquet kitchen. I was happy for it, my first real job. I didn’t think about the Greeks, about Plato or Aristotle. Those dudes pooh-poohed any notion of work, especially anything more physical than pontificating in a toga.

So that hotel job didn’t pay enough for a yacht. But it helped with journalism school.

Prior, I’d worked at the family business. This included the garden, a hopeless piece of earth so large that the gravitas of its vegetables, years later, gave way to a handful of houses complete with fair-sized yards. After the great garden’s bondage, a hotel kitchen was The Promised Land.

Eventually I started writing for newspapers. So I’m still not getting seriously rich. This might also be because I feel closest to my centre when I’m at my laziest.

Now work and money should go hand-in-hand. And by money I’m thinking what you’re thinking, that is more money in-hand. Even so, it seems we’re wired for more than money.

Suspicious views on these matters have always been around. One human origin story from ancient Babylon involves the god Marduk, who supposedly created our world from the body of a slain enemy. Then he made humans for the grunt work of caring for the place, a job he didn’t care about. How’s that for work incentive sucked from your human soul?

I suspect the reality is closer to this. There’s a world. We’re placed in it. We maintain it. (Apparently not well.) But our work is less about a curse and more about being co-workers, even co-creators, alongside an active and caring Maker. This makes work, at least as originally intended, a relational gift.

We can appreciate what the psychologists call “flow,” falling into work like you might fall into a dream. Sometimes work even has more of a sustained rhythm, a spiritual bliss. And that idleness? (Let’s call it idleness, not laziness.) Without it we’d get lost in the weeds, no quiet or space to see things half-clearly.

So maybe good work is like connecting with a good love, a relationship bringing meaningful things. Some good humour, with any luck. Even new life. Still, there’s a reason why the birthing process is called “labour.”

Which brings us back to gardening. I made peace with all this, as much as anyone might, anyway, when I was a young reporter. I bought a simple garden hoe, painted it gold, and, as a wedding gift, gave it to my father when he married his second wife. Despite my shaky relationship with that hopeless garden, at the wedding I then shared what the place taught me.

Thirty years on, with my father now in eternity, that same golden hoe is somehow back with me. It’s now in my backyard with a garden sign saying, “Sow, weed, water and wait.” They wouldn’t sell much if it said, “Work whatever ridiculous ground you’re given, because, really, what choice is there?”

We know we’re not in any Garden of Eden. It seems we’re not meant to be. Labour Day is one reminder. But it’s also a rather fine time to celebrate our various work, anyway.

Sow. Weed. Water. You know. It’s golden.

Always love your perspective on life, Thom. I remember many years ago working (more helping out) on my grandfather’s farm. I would always get the “job” of weeding the garden. But the words he said back then ring just as true to me today. “You don’t work…you don’t eat.”

It’s true. And nobody knows what that’s like anymore, being so close to the food we eat.