(The Hamilton Spectator – Saturday, October 7, 2017)

It was a recent evening at the University of Toronto when I was reminded of it all, that hope is better than skepticism, that faith is better than doubt, that love (in the abiding sense of charitable love) is better than fear.

I was reminded, too, how I’ve always felt more kinship with people who journey through life with honest doubts, than with people having belief systems that are so glib, that, if they were suspenders, would be unable to hold up their pants on a blustery day.

The wind, after all, is a dilemma for both skeptic and believer.

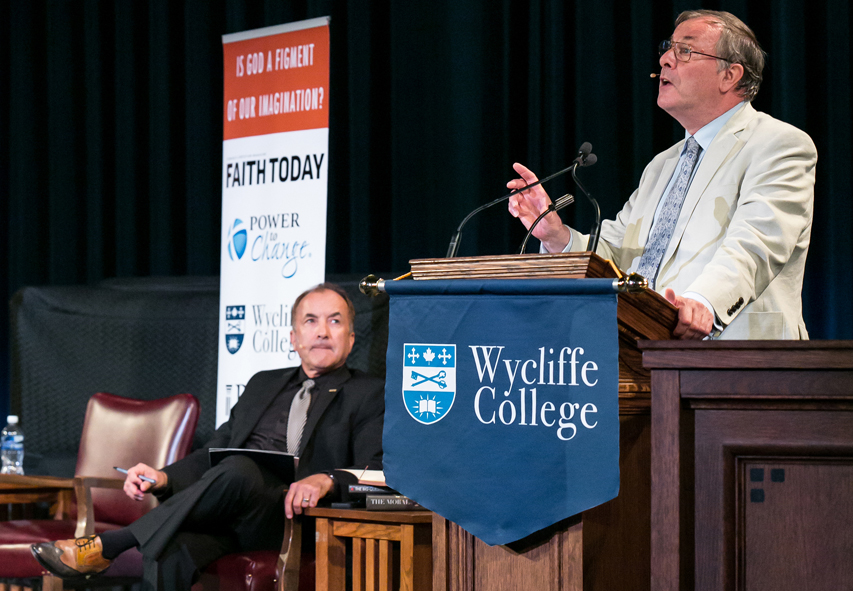

These thoughts arose after I joined 1,000 others in an old hall at the U of T to hear a public debate between an atheist (who, interestingly, was previously a Christian) and a Christian (who, equally interestingly, was previously an atheist.)

Their question for the evening? “Is God a figment of our imagination?” You might as well ask, “So who has seen that wind?”

Consider that 50 years ago on October 7 a heavy wind blew the golf ball of golfer Robert Mitera 447 yards for the world’s longest hole-in-one. Or consider on October 7, 280 years ago, another wind contributed to 40-foot waves off the coast of India, sinking 20,000 small boats and killing 300,000 people.

No, not even the brightest learner at Hogwarts, sitting in the light of stained glass and the smell of timeless books, knows where the wind comes from or what it might do next.

The atheist, though, wonders, as he did in that debate, why God gets the glory and thanks for one child saved from, say, a hurricane, but never the blame for the many dead children. What about childhood leukemia? Or that deadly car accident? (Or a mass shooting in Las Vegas?)

The questions are fair for anyone who’s thought much about anything in this old world. No, there has to be something more. Something different. And there is, said the Christian in that debate.

“Shit happens,” is how he put it. It happens with disturbing randomness.

But the narrative of the Creator incarnating into human form shows that God understands the human condition intimately. And that narrative, if true, is a game changer. It creates a way to find meaning and purpose, and a way through suffering. In this, genuine thanksgiving is possible.

“So let’s keep our questions open,” he said. Because if we ask the wrong questions with the wrong tools (How far is it to the colour yellow? Or, how heavy is one hour?) then we won’t get satisfying answers.

The atheist wondered aloud why God would become a human to sacrifice himself at the hands of himself to save humans from himself.

And so it went. Back and forth.

“We’re running out of time to solve this God thing,” said the moderator, and before we knew it everyone was eating sandwiches, then leaving, the lost and found, both, finding their way home in the darkness, carrying their thoughts with them.

The entire affair was civil and respectful in fashion showing what a Canadian university can be in its best moments. It was the U of T’s theological school, Wycliffe College, that brought in the pair: Michael Shermer, the American academic and editor-in-chief of Skeptic Magazine, and Alister McGrath, the Christian humanist from Oxford University.

If only we’d experience more of such open dialogue, regardless of shade of faith, or lack of. (Because doesn’t life, like art, if it’s art worth anything, need both light and shadow?)

It was Kierkegaard who said that no person has the right to delude another into the belief that faith is something of no great significance, that it’s an easy matter, when, in truth, it’s among the greatest and most difficult things in life.

And Sartre said both believer and doubter need to take their dark and searing vision into account, otherwise either or both will be left frail and shallow.

Thanksgiving, it seems to me, is a suitable time to consider these truths, maybe the most suitable time.

Amidst politically correct fears so common in Canadian universities, I imagine that enough thinking young people would be especially thankful. Thankful for refreshing and safe spaces where they can listen and speak honestly in their own language.

And maybe even feel the wind.