Thomas Froese Photo

(The Hamilton Spectator – Saturday, September 3, 2022)

If we were all old men we could do worse than land in Ernest Hemingway’s classic novella The Old Man and the Sea. The story, among the most loved of the 20th century, just turned 70.

The old man – his name is Santiago – is an outsider. He’s impoverished. Has horrible luck. Hasn’t caught a fish for 84 days. Is he cursed? People think so. Still, his eyes are cheerful and undefeated. He often dreams of his boyhood, and lions on the white beaches of Africa.

One morning after such dreaming he drinks coffee with his only friend, a faithful Cuban boy, Manolin. The boy loves the old man, and his stories about baseball. The old man then sets out, again, to fish. He’ll be wise. Skilled. Precise. Patient. This will be his day.

Naturally, a fish comes along. And what a fish. What then unfolds is important. Even today. Especially today, when we can so easily amuse ourselves to death. So is the story about youth and old age? Love and kinship? Beauty and violence? Luck and skill? Yes. More so, it’s about the human spirit. Living with grace under pressure.

“A man can be destroyed, but not defeated,” is one of Santiago’s thoughts. It’s grasped especially by Ugandan students when I’ve taught this story in that part of the world. Grace and composure in the daily fight of life is understood there because, as you might imagine, Ugandan lives are often more like the old man’s life.

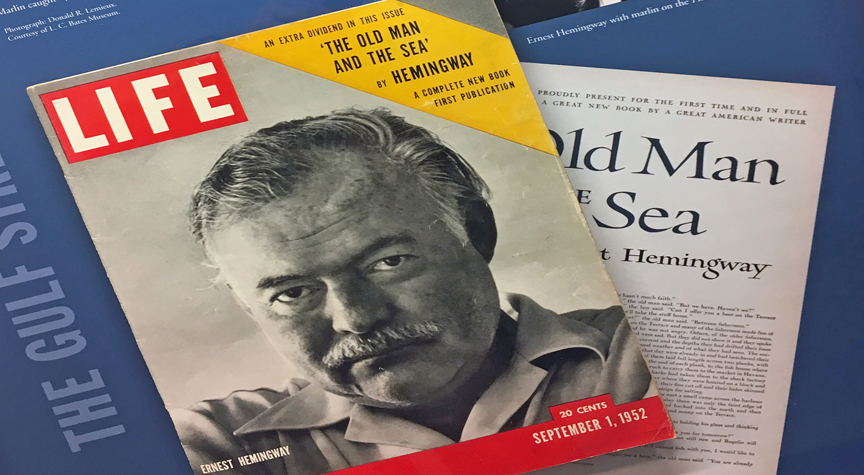

But this fish story is for anyone, a reminder how we’re not alone in our struggles. That’s why when it first appeared in Life Magazine on Sept. 1, 1952, five million copies sold in two days. It went viral, so to speak. Santiago, pursuing the catch, beating back the sharks, becoming the everyman, characterizing me, or you, or the neighbours.

Hemingway said it’s “the best I can write ever for all my life.” After some career lows, it helped bring him the 1954 Nobel Prize for Literature, a lifetime honour. Validation. Destroyed but not defeated. Earlier that year, speaking of Uganda, the writer suffered head injuries and a near-death experience – the press had written his obituary – after back-to-back plane crashes in that East African nation. Then declining health.

The American writer had started as a correspondent for the Toronto Star before writing literary fiction for more than 30 years from experiences in Europe, East Africa, and the Gulf Stream. That’s where he created the character Santiago.

Hemingway also, you may know, fought his personal demons. Even so, his voice remains. “All you have to do is write one true sentence,” he once said. “Write the truest sentence you know. So finally I’d write one true sentence, then go on from there. It was easy then because there was always one true sentence I knew, or had seen, or had heard someone say.”

This is when art transcends, when you tap into something larger than yourself. In this the artists, the good ones, look past the headlines (and the world has seen some hard headlines in recent years) to what’s now possible. They reimagine things. They help the rest of us mourn what’s been lost, but then also invite new things. New life.

Of course, the work is never finished. Hemingway himself left thousands of pages (and this in the age of the manual typewriter) of unpublished work. Making peace with what’s unfinished is also part of this.

The Old Man and the Sea isn’t a long read. It took just 20 pages, with illustrations, in that 1952 Life Magazine. Today you can easily listen to it on your phone, or search its title with “free text version” to find it online. It’s a way to say, “Hey, old man. Happy birthday!”

No, really. Isn’t this weekend a good time to pause? To recalibrate? In some chair, or better, at some nearby beach? Soon, after all, it’s back to school.